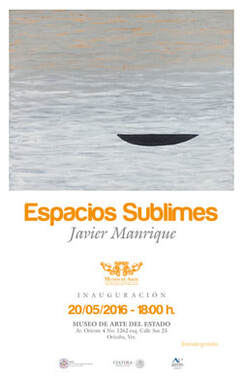

The Origin of the Journey

Javier Manrique’s painting suggests an inquiry into minute signs that reference a fusion of

the road with the idea of origin, combining to produce a whole. So, there is no origin, and thus, no

path to travel; rather the journey always is the starting point, and remains so with regard to vast

expanses: the land, the sea, the sky. The signs Manrique places in space mostly appear to be

suspended: a suspension that is a kind of inmutability, perhaps originating in the earliest gestures,

the original lines, an ancestral language. The allusion to petroglyphs and other archaic signs—which

could derive equally from indigenous textiles, codices, rudimentary maps, certain “universal”

symbols related to children’s drawings—locates the artist on a primitive horizon where painting is an

act of audacity against the world.

The use of the word audacity necessarily implies the existence of risk. Manrique constantly

alludes to risk in his painting. He submerges the viewer in spaces that suggest absolute values (the

absolute could sometimes be his fields of color, while at other times, his signs: a lighthouse, a sea

vessel, an ominous cloud,) profound experiences (like the solitary encounter with a temple) or the

more elemental situation of finding oneself at the edge of the sea, entering the waters (a situation

that could be as banal as it would be hazardous,) or rising into the sky or crossing a desert, one step

after another. Inasmuch as the journey contains its own origin, the “surmountable” does not pose

the risk, but rather, that which is “constitutive.” For Manrique’s audacity is revealed to be a pictorial

act: there are no signs without substance, no trivial images, not a single insignificant stroke; the

painter calls to us from the depths of a common visual memory, one that could originate in cave

walls as easily as in a caution sign on the highway. Manrique opts for the most self-evident

symbology: the bowl-shaped sea vessel afloat on the water, the flying bird with outspread wings

derived from textiles and Navajo necklaces, arrows indicating directions. The vein passing through

this audacity is that of freedom: a freedom in search of its own tradition.

In searching for, and finding, those primordial pictorial gestures, Javier Manrique anchors

himself in an economy of means that rubs up against minimalism, on the one hand, and the

constructive universalism of Joaquín Torres-García, on the other. In either case, it is a search for

elemental meaning. Here, the encounter of the subject with its tradition is joined, not as an

integration of the “ego” with the “other,” but with “oneself,” which is all the rest of us. For that

reason, the experience of attending Manrique’s exhibits is one of belonging. The sensation of being

a part of that extreme solitude, keeping a precarious d afloat on the vastness of the waters; of

that mountainous sillhouette, scissors practically cutting it out against the sky; the sensation of

sharing the distant journey of a horseman under the curtain of rain; retracing the migrant’s journey

across an endless desert; of finding a single geometric figure in a field of color, as if this shape might

anchor the whole of reality. All this is risky, and it is all audacious; it’s all the journey of the origin.

The fusion of origin and journey—which finds its condensed form in traditional language as “origin is

destiny”—achieves its high point in Javier Manrique’s painting in the plasticity of a bird—the Navajo

bird, again—that climbs to the pinnacle of the sky. But in fact it is not the sky that fills the space at

the top of the painting: the earth and sea are overhead, while the cloud-filled sky extends across the

bottom. Some might call this the height of audacity, but perhaps it is, in essence, no different from

painting bisons and horses on the roof of a cave. Suddenly we find ourself face to face with an

image of something that belongs to us, and which we will never manage to comprehend unless we

turn our journey into the origin: the image of the whole.

Jaime Moreno Villarreal

(tr. Mark Schafer)

Javier Manrique’s painting suggests an inquiry into minute signs that reference a fusion of

the road with the idea of origin, combining to produce a whole. So, there is no origin, and thus, no

path to travel; rather the journey always is the starting point, and remains so with regard to vast

expanses: the land, the sea, the sky. The signs Manrique places in space mostly appear to be

suspended: a suspension that is a kind of inmutability, perhaps originating in the earliest gestures,

the original lines, an ancestral language. The allusion to petroglyphs and other archaic signs—which

could derive equally from indigenous textiles, codices, rudimentary maps, certain “universal”

symbols related to children’s drawings—locates the artist on a primitive horizon where painting is an

act of audacity against the world.

The use of the word audacity necessarily implies the existence of risk. Manrique constantly

alludes to risk in his painting. He submerges the viewer in spaces that suggest absolute values (the

absolute could sometimes be his fields of color, while at other times, his signs: a lighthouse, a sea

vessel, an ominous cloud,) profound experiences (like the solitary encounter with a temple) or the

more elemental situation of finding oneself at the edge of the sea, entering the waters (a situation

that could be as banal as it would be hazardous,) or rising into the sky or crossing a desert, one step

after another. Inasmuch as the journey contains its own origin, the “surmountable” does not pose

the risk, but rather, that which is “constitutive.” For Manrique’s audacity is revealed to be a pictorial

act: there are no signs without substance, no trivial images, not a single insignificant stroke; the

painter calls to us from the depths of a common visual memory, one that could originate in cave

walls as easily as in a caution sign on the highway. Manrique opts for the most self-evident

symbology: the bowl-shaped sea vessel afloat on the water, the flying bird with outspread wings

derived from textiles and Navajo necklaces, arrows indicating directions. The vein passing through

this audacity is that of freedom: a freedom in search of its own tradition.

In searching for, and finding, those primordial pictorial gestures, Javier Manrique anchors

himself in an economy of means that rubs up against minimalism, on the one hand, and the

constructive universalism of Joaquín Torres-García, on the other. In either case, it is a search for

elemental meaning. Here, the encounter of the subject with its tradition is joined, not as an

integration of the “ego” with the “other,” but with “oneself,” which is all the rest of us. For that

reason, the experience of attending Manrique’s exhibits is one of belonging. The sensation of being

a part of that extreme solitude, keeping a precarious d afloat on the vastness of the waters; of

that mountainous sillhouette, scissors practically cutting it out against the sky; the sensation of

sharing the distant journey of a horseman under the curtain of rain; retracing the migrant’s journey

across an endless desert; of finding a single geometric figure in a field of color, as if this shape might

anchor the whole of reality. All this is risky, and it is all audacious; it’s all the journey of the origin.

The fusion of origin and journey—which finds its condensed form in traditional language as “origin is

destiny”—achieves its high point in Javier Manrique’s painting in the plasticity of a bird—the Navajo

bird, again—that climbs to the pinnacle of the sky. But in fact it is not the sky that fills the space at

the top of the painting: the earth and sea are overhead, while the cloud-filled sky extends across the

bottom. Some might call this the height of audacity, but perhaps it is, in essence, no different from

painting bisons and horses on the roof of a cave. Suddenly we find ourself face to face with an

image of something that belongs to us, and which we will never manage to comprehend unless we

turn our journey into the origin: the image of the whole.

Jaime Moreno Villarreal

(tr. Mark Schafer)