The Outlined Profile, the Trodden Path.

The Imprint & the “Fictional-graphics” of Memory.

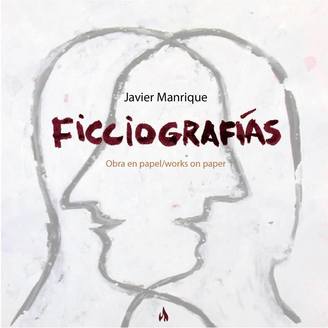

When Javier Manrique outlines his characters, he makes visible a series of self-reflections on the possibilities experienced by each of us while our own identity is shaped through the constant repetition of some memories-traces, memories-images, memories-captured instants. In a subtle way, these reflections are taken to the paper and we, the viewers, are given a framework, a map, a territory, and a set of instructions for us to begin treading—as much as it be possible—upon the path of our own reflections and to set out on the ever-constant journey of building ourselves.

The Mexican-American engraver’s ethereal representations suggest—as soon as they are placed on the surface of the paper—a delicate transition from hand to ink, from ink to plate, from plate to paper surface; and, again, from hand to ink, from ink to plate… The image of the search and the reencounter implied in the trace—precise, however brief it may be—left by all memory formation is conveyed through a constant movement of lines, colors, weaves, textures, and atmospheres onto the paper. And this is suggested at Manrique’s hand through his use of lines, outlines, and his careful way of applying color areas on the surface as someone who pours a fish into the sea, as someone describing the movement of the wings of a butterfly, as someone whispering words before going to sleep...

Reminiscences, the imprint of a mental image, the trace of an experience taken into a bi-dimensional language and then crystallized as a memory are the guiding themes of the set of works compiled here. And, yet, this configuration of memory upon which the identity of each of us will be anchored seems to spin—in this specific case—over its spatial categories rather than over its temporal ones. To be more precise, I’d like to quickly recall now the work of the artist when he paints using an easel and to establish a contrast—or a complementarity—with his graphic artworks. Although both allude to a self-reflective exercise on the consolidation of identity experienced by all human beings as we shape ourselves, live, and recreate, I find two diverging directions—different even in terms of its techniques—in relation to such process.

In his easel artwork, he questions the relation between the being and the space; and in his graphic artwork this question is, rather, directed towards the relation between the being and the passage of time (or the way time is captured). By interweaving fiction and veracity, the image functions as a monument, as a reactivator of events, as a banner facing the passage of time. In face of the avalanche of oblivion—memory. In face of that waterfall which fades lines as it moves down—the constant evocation of an image. In face of a picky fate which places us in-between diverse mental blackouts—the endeavor to shape, over and over again, our own outlines, our own histories-stories, our own identities. And even though recollections may be nothing but a suggestion, the perception of a silhouette or an atmosphere, however painful they may be, and even though they may occur only once and as a fruit—to a great extent—of mere chance, it is worthwhile to make an effort and recreate, represent, relive whatever we are able to keep in our memory, however brief, fleeting, and fragile it may be.

Within this mnemotechnic path, memories are also presented as whimsical characters. And, perhaps because of it, Manrique’s lines give the impression of having been made fast, at just the right moment when they begin to become a part of the past. The present time is frozen through traces which try to reconcile that instant in which an event stops being present and it becomes a part of the past. In this sense, it would be good to point out that many times memories are chanceful work materials—they arrive whenever they please and sometimes we just remember a few things, pleasant or unpleasant; while sometimes, we want to remember something and we simply can’t. Thus, all the virtual, abstract, and subtle spaces which shape us can be materialized by repeating similar motifs, by constantly imagining characters, or by going back in time to analogue atmospheres. Reoccurrence as a memory exercise somehow works for pinning down two equally fleeting elements—time and memory.

Finally, I would like to mention a final theme—the sense of belonging to which we aspire when we tread back upon steps already taken. In such action, there is shift, a transit. And, in order to do it, Manrique also provides us with mobile elements (an airplane, a bicycle, our own body) as a brief catalogue of vehicles we can use to look for those mental images-lines which shape us. Thus, he facilitates for us a reflective movement which allows us to walk back upon our own footprints (including some waiting moments, and some situations of fragility and absence) and go back to that initial point in which we are ourselves, to the peculiar geography of our own face. And perhaps the arrival point is not a physical place at all; perhaps, the finality is—at the end of the day—to travel from the present time to another time in search of that man, or woman, who is not exactly us but is not exactly someone else either. An “us” which is infinitely distanced and, at the same time, infinitely close—deeply mobile and subtly static. A humanly paradoxical “us” placed between our constant forgetfulness and our fleeting memories.

Ma. Jimena Ortiz Benítez

(tr. Tiosha Bojorquez Chapela)

The Imprint & the “Fictional-graphics” of Memory.

When Javier Manrique outlines his characters, he makes visible a series of self-reflections on the possibilities experienced by each of us while our own identity is shaped through the constant repetition of some memories-traces, memories-images, memories-captured instants. In a subtle way, these reflections are taken to the paper and we, the viewers, are given a framework, a map, a territory, and a set of instructions for us to begin treading—as much as it be possible—upon the path of our own reflections and to set out on the ever-constant journey of building ourselves.

The Mexican-American engraver’s ethereal representations suggest—as soon as they are placed on the surface of the paper—a delicate transition from hand to ink, from ink to plate, from plate to paper surface; and, again, from hand to ink, from ink to plate… The image of the search and the reencounter implied in the trace—precise, however brief it may be—left by all memory formation is conveyed through a constant movement of lines, colors, weaves, textures, and atmospheres onto the paper. And this is suggested at Manrique’s hand through his use of lines, outlines, and his careful way of applying color areas on the surface as someone who pours a fish into the sea, as someone describing the movement of the wings of a butterfly, as someone whispering words before going to sleep...

Reminiscences, the imprint of a mental image, the trace of an experience taken into a bi-dimensional language and then crystallized as a memory are the guiding themes of the set of works compiled here. And, yet, this configuration of memory upon which the identity of each of us will be anchored seems to spin—in this specific case—over its spatial categories rather than over its temporal ones. To be more precise, I’d like to quickly recall now the work of the artist when he paints using an easel and to establish a contrast—or a complementarity—with his graphic artworks. Although both allude to a self-reflective exercise on the consolidation of identity experienced by all human beings as we shape ourselves, live, and recreate, I find two diverging directions—different even in terms of its techniques—in relation to such process.

In his easel artwork, he questions the relation between the being and the space; and in his graphic artwork this question is, rather, directed towards the relation between the being and the passage of time (or the way time is captured). By interweaving fiction and veracity, the image functions as a monument, as a reactivator of events, as a banner facing the passage of time. In face of the avalanche of oblivion—memory. In face of that waterfall which fades lines as it moves down—the constant evocation of an image. In face of a picky fate which places us in-between diverse mental blackouts—the endeavor to shape, over and over again, our own outlines, our own histories-stories, our own identities. And even though recollections may be nothing but a suggestion, the perception of a silhouette or an atmosphere, however painful they may be, and even though they may occur only once and as a fruit—to a great extent—of mere chance, it is worthwhile to make an effort and recreate, represent, relive whatever we are able to keep in our memory, however brief, fleeting, and fragile it may be.

Within this mnemotechnic path, memories are also presented as whimsical characters. And, perhaps because of it, Manrique’s lines give the impression of having been made fast, at just the right moment when they begin to become a part of the past. The present time is frozen through traces which try to reconcile that instant in which an event stops being present and it becomes a part of the past. In this sense, it would be good to point out that many times memories are chanceful work materials—they arrive whenever they please and sometimes we just remember a few things, pleasant or unpleasant; while sometimes, we want to remember something and we simply can’t. Thus, all the virtual, abstract, and subtle spaces which shape us can be materialized by repeating similar motifs, by constantly imagining characters, or by going back in time to analogue atmospheres. Reoccurrence as a memory exercise somehow works for pinning down two equally fleeting elements—time and memory.

Finally, I would like to mention a final theme—the sense of belonging to which we aspire when we tread back upon steps already taken. In such action, there is shift, a transit. And, in order to do it, Manrique also provides us with mobile elements (an airplane, a bicycle, our own body) as a brief catalogue of vehicles we can use to look for those mental images-lines which shape us. Thus, he facilitates for us a reflective movement which allows us to walk back upon our own footprints (including some waiting moments, and some situations of fragility and absence) and go back to that initial point in which we are ourselves, to the peculiar geography of our own face. And perhaps the arrival point is not a physical place at all; perhaps, the finality is—at the end of the day—to travel from the present time to another time in search of that man, or woman, who is not exactly us but is not exactly someone else either. An “us” which is infinitely distanced and, at the same time, infinitely close—deeply mobile and subtly static. A humanly paradoxical “us” placed between our constant forgetfulness and our fleeting memories.

Ma. Jimena Ortiz Benítez

(tr. Tiosha Bojorquez Chapela)