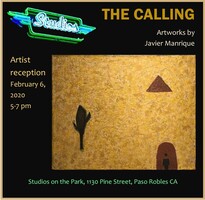

I walk into Studios on the Park on an unusually cold Paso Robles day, and head toward the back of the gallery where the workshop studio is located. As I move through the gallery I see Javier Manrique's paintings lining the walls. The works make up his exhibit, The Calling, on display at the Pine Street gallery until March 1.

Inside the workshop studio, tables are set with 6-by-6 inch tiles, one in front of each seat. Another table toward the back is overflowing with art supplies: pigmented paints in variously sized glass jars, paint brushes, palette knives, and buckets filled with a mysterious, fine-grained substance. Manrique, our leader for the day, puts the final touches on his workshop setup as he awaits his attendees.

Manrique—an acclaimed, San Francisco-based artist who works in both the U.S. and Mexico—is preparing to teach the art of fresco, a unique medium for which he is well known. Though not as commonly employed today, some of the most famous works of art in the world were made through this ancient process involving limestone and watercolors. Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam is a household name, but what's less widely known is that this Renaissance work is a fresco painting.

"Fresco is probably the most ancient form of painting," Manrique tells me. "It comes from the caves, and many different cultures around the world have some sort of fresco painting. It's part of human history."

The fresco process begins by mixing lime with sand, which creates a fresh plaster. The plaster is then smoothed onto the desired surface. In the case of Manrique's Feb. 8 workshop, we used individual tiles, but the medium is most commonly used for larger projects. Next, highly pigmented watercolors are used to paint directly onto the wet plaster. Once the plaster dries, the paint crystallizes with the limestone, resulting in an inseparable painting.

Because fresco requires the wet plaster to be applied to a stable surface—like a tile, wall, or ceiling—the end result is not as easily transportable as the typical canvas painting. For this reason, Manrique's current exhibit at Studios on the Park focuses more on the other media he uses, such as oil and encaustic painting (though the exhibit does include three fresco works). Encaustic painting, like fresco, is a mixed-media technique. In this case, the painter mixes hot wax with colored pigments before applying the mixture to the canvas.

In Tell Them I'm Sleeping, an oil work hung in his Studios exhibit, Manrique uses a neutral color scheme and a canvas broken into four quadrants. Some of the images in the painting, such as a gray ladder, traverse two of the canvases. Others stop abruptly as they reach the edges. A profile of a human head recurs in the painting, facing upward and to the side. Though the symbols that occupy each canvas seem simple when taken on their own—a head, a ladder, a bundle of flower-like objects—the four canvases brought together seem to tell a story. It's similar to the way that a graphic novel requires that its panels—the individually drawn frames—be viewed together on a page for the story to make sense.

By no coincidence, Manrique also does graphic work, which fits right in with the multi-panel approach that he engages in many of his paintings. He said that a young writer he met in Mexico once drew a distinction between his paintings and his graphic work that he found particularly resonant with his art. "She said that my graphic work tends to be more of a chronology of time, using figurative images, archetypes, and symbols to give an idea of some situation within time," Manrique said. "In the paintings, she mentions, it is more about one's place in space."

It's this understanding of one's own positionality that Manrique hopes viewers will take away from his work. "Art is an essential part [of you], if you let it be. I can help you along your own path," he said. "So if my work can help you understand yourself better, that's what I would like." Δ

Inside the workshop studio, tables are set with 6-by-6 inch tiles, one in front of each seat. Another table toward the back is overflowing with art supplies: pigmented paints in variously sized glass jars, paint brushes, palette knives, and buckets filled with a mysterious, fine-grained substance. Manrique, our leader for the day, puts the final touches on his workshop setup as he awaits his attendees.

Manrique—an acclaimed, San Francisco-based artist who works in both the U.S. and Mexico—is preparing to teach the art of fresco, a unique medium for which he is well known. Though not as commonly employed today, some of the most famous works of art in the world were made through this ancient process involving limestone and watercolors. Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam is a household name, but what's less widely known is that this Renaissance work is a fresco painting.

"Fresco is probably the most ancient form of painting," Manrique tells me. "It comes from the caves, and many different cultures around the world have some sort of fresco painting. It's part of human history."

The fresco process begins by mixing lime with sand, which creates a fresh plaster. The plaster is then smoothed onto the desired surface. In the case of Manrique's Feb. 8 workshop, we used individual tiles, but the medium is most commonly used for larger projects. Next, highly pigmented watercolors are used to paint directly onto the wet plaster. Once the plaster dries, the paint crystallizes with the limestone, resulting in an inseparable painting.

Because fresco requires the wet plaster to be applied to a stable surface—like a tile, wall, or ceiling—the end result is not as easily transportable as the typical canvas painting. For this reason, Manrique's current exhibit at Studios on the Park focuses more on the other media he uses, such as oil and encaustic painting (though the exhibit does include three fresco works). Encaustic painting, like fresco, is a mixed-media technique. In this case, the painter mixes hot wax with colored pigments before applying the mixture to the canvas.

In Tell Them I'm Sleeping, an oil work hung in his Studios exhibit, Manrique uses a neutral color scheme and a canvas broken into four quadrants. Some of the images in the painting, such as a gray ladder, traverse two of the canvases. Others stop abruptly as they reach the edges. A profile of a human head recurs in the painting, facing upward and to the side. Though the symbols that occupy each canvas seem simple when taken on their own—a head, a ladder, a bundle of flower-like objects—the four canvases brought together seem to tell a story. It's similar to the way that a graphic novel requires that its panels—the individually drawn frames—be viewed together on a page for the story to make sense.

By no coincidence, Manrique also does graphic work, which fits right in with the multi-panel approach that he engages in many of his paintings. He said that a young writer he met in Mexico once drew a distinction between his paintings and his graphic work that he found particularly resonant with his art. "She said that my graphic work tends to be more of a chronology of time, using figurative images, archetypes, and symbols to give an idea of some situation within time," Manrique said. "In the paintings, she mentions, it is more about one's place in space."

It's this understanding of one's own positionality that Manrique hopes viewers will take away from his work. "Art is an essential part [of you], if you let it be. I can help you along your own path," he said. "So if my work can help you understand yourself better, that's what I would like." Δ